Netscape launched interactivity into web pages in 1995, via a new scripting language called JavaScript. This heralded the start of the multimedia era of web browsers. In March 1996, Netscape debuted its Navigator 2.0 browser, which included JavaScript 1.0 and the first inklings of what would become a fundemantal model of web programming: the Document Object Model (DOM). But Netscape wasn’t finished with 1996 just yet. What they launched next is the subject of this post, the third in our series about the history of JavaScript.

Netscape Navigator 3.0 was released in August 1996. It featured “fully integrated video, audio, 3D, and Internet telephone communications capabilities.” Under the hood, there were some key JavaScript and HTML enhancements — which we will discuss below.

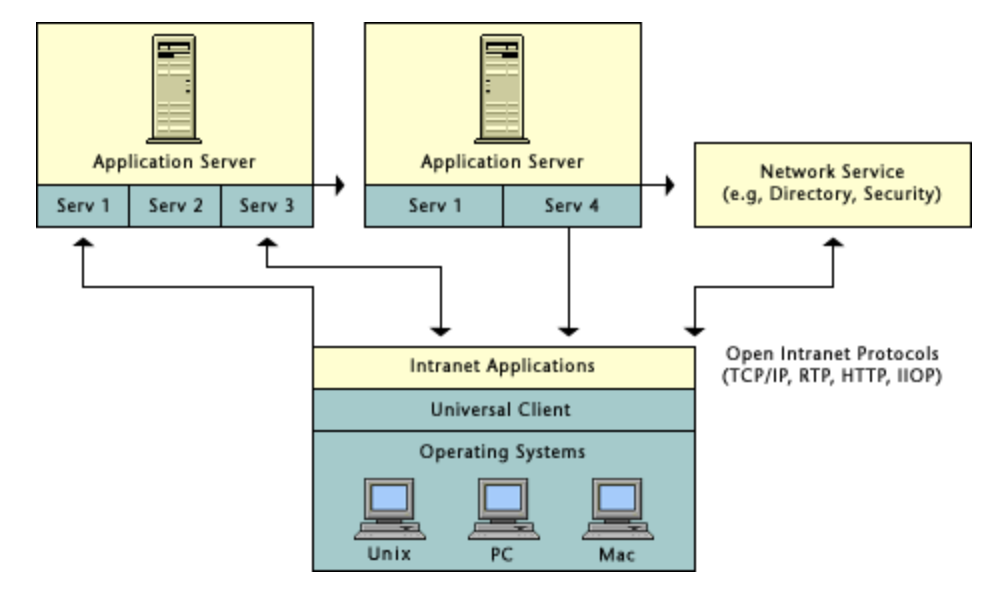

Netscape had big plans for its 3.0 browser. It was seen as a “universal client” to help expand what HTML could do. But Netscape was also looking to broaden its product offering with a suite of tools it called Netscape Communicator, which it began pitching to developers later in 1996. The ultimate goal was to pioneer a new type of software product: “network-centric applications.”

Netscape ONE & The Emergence of Web Apps

There was almost something Microsoftian about Netscape’s ambition at this point. On 1 August, 1996, Marc Andreessen wrote in his online column about a new product called Netscape ONE:

“This week Netscape and 50 other vendors introduced Netscape ONE, the open network environment. Netscape ONE provides a rich set of tools and functionality to create a new generation of software: network-centric applications.”

In the Netscape ONE white paper, Netscape attempts to re-frame HTML from a simple document markup language to “a universal container for an application.” The boundaries were starting to be pushed regarding the purpose of a web page — and the functionality it could offer. A web page wasn’t just for presenting information anymore, Netscape was saying. It was now also a “container” for business applications.

If HTML had become a universal container, Netscape Navigator was now “the universal client for publishing, navigation, collaboration, and application access.”

Indeed, Navigator 3.0 was being pitched as a key tool in the expansion of HTML:

“Today, Netscape Navigator 3.0 continues to expand the capabilities of HTML with new features such as borderless frames, fonts, and better table support to further increase the power of HTML-based client interfaces.”

The shift to what Netscape called “HTML applications” is made explicit in the ONE paper with statements like this:

“Similar to the way in which OS-specific resource files describe interfaces using dialogs, fields, buttons, and so on, HTML is developing into a platform-independent resource definition language to specify interfaces and assemble applications from components.”

An example is given, Juggler Toys, where “HTML acts as a universal container for an application comprising three HTML controls, two Java applets, and some native code components.” Nowadays we’d call this a “web app,” but it’s interesting to see how it all began as a patchwork of HTML, JavaScript, Java applets and “native code components” (a.k.a. plug-ins).

JavaScript 1.1

Included in both Navigator 3.0 and Netscape ONE was version 1.1 of JavaScript, which was still being positioned as a complement to the more powerful web programming language Java. According to the white paper:

“As the scripting language of the Internet, JavaScript complements the power of executing compiled Java applets. JavaScript is a security-enabled, platform-independent scripting language related to Java but considerably simpler to use.”

Apart from continuing the spurious claim that JavaScript was “related to Java,” it’s notable that Netscape still viewed it as the little brother of Java. Real programmers should use Java, was the implication, whereas JavaScript was for “application authors who are not professional programmers.”

Feedback was generally positive about the latest version of JavaScript, which was released in August with Navigator 3.0. An InfoWorld review by Gordon McComb in October 1996 said that it was “more mature and refined this time around, with many of its “version 1.0” bugs squashed.” 1.1 also brought enhancements:

“What’s more, JavaScript supports a number of enhancements, including new object constructors, in-place image replacement, and direct communication between it and Java applets and plugins. Though JavaScript is far from being complete, it has taken another step in becoming a world-class user scripting language.”

Perhaps the most significant update in 1.1 was the ability to create JavaScript libraries as separate pages. So instead of having to insert the JavaScript code into the HTML file, you could put it in a .js file and call it in a <SCRIPT> tag within the HTML. This would have huge implications in the years to come, with JavaScript libraries like jQuery, AngularJS and React taking the web by storm in the 2000s.

Netscape Developers Conference

In October 1996, in New York City, Netscape held its second Internet Developer Conference (the first was in March), to talk up Netscape ONE among other things. A lot of the focus was on “enterprise developers,” who were busy building intranets for companies. Marc Andreessen set the scene in his keynote:

“We think there’s a really fundamental shift underway, due to the internet and due to intranets, that’s going to drive a lot of technological change and a lot of business opportunity for all of us, in the months and years ahead. The cornerstone of this is the fact that HTML — which grew up as the rich language, document format of the web — is now expanding way beyond browsing. It’s now serving as a basis for web-based email, also groupware, and also full-fledged business applications.”

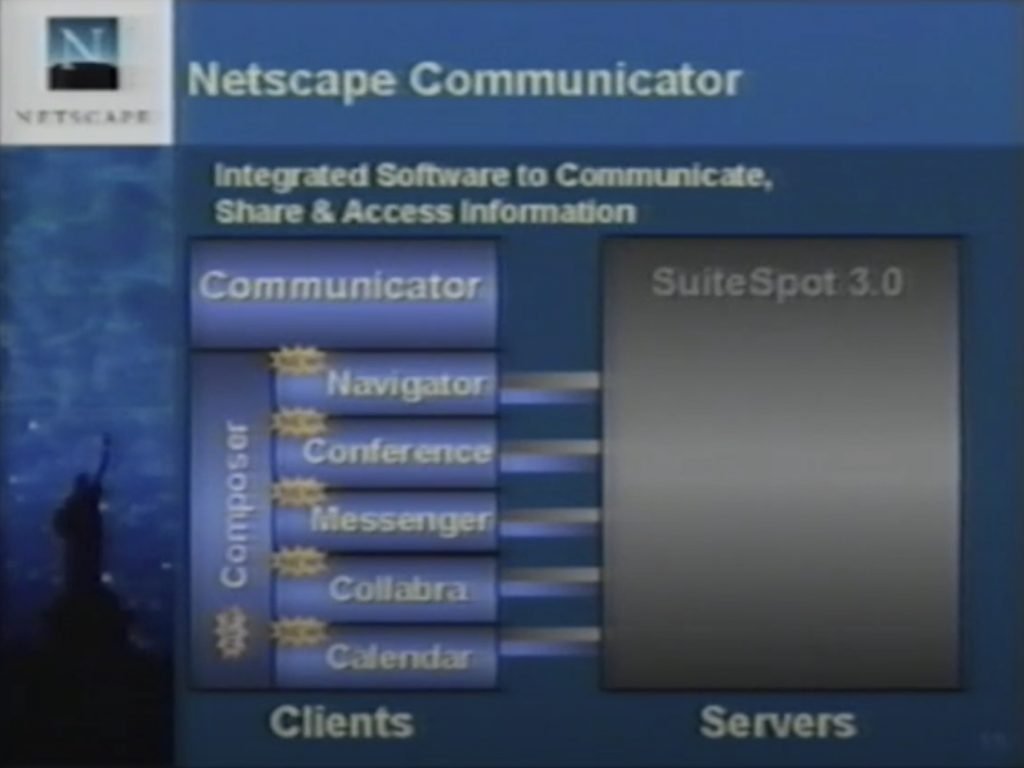

The same week that Netscape held its second developer conference, the company also announced its next major product: Netscape Communicator, scheduled for release in 1997. Communicator would incorporate version 4 of Netscape’s flagship browser, Navigator, and add other office products. Essentially, it was a re-branding of Netscape’s core product offering — from Netscape Navigator to Netscape Communicator. This reflected the expansion of web functionality that Andreessen referenced in his keynote, from documents (web pages) to web applications and corporate networking features like groupware.

He listed five new components, all of which we can view a quarter century later as early versions of web products we now use daily — for example, via Google’s online office suite. First Andreessen mentioned email in a browser (Gmail today), groupware called Netscape Collabra (Google Groups), conferencing software “for real-time audio and data conferencing over intranet” (Google Meet), an online calendar (take a guess…), and “an easy-to-use HTML editing tool called Netscape Composer” (Google Docs is the closest equivalent now).

Andreessen then listed a raft of server-side products that Netscape was also announcing, to complement Netscape Communicator. This is where Netscape hoped to make money, as it competed with Microsoft on the client-side with their respective free web browsers.

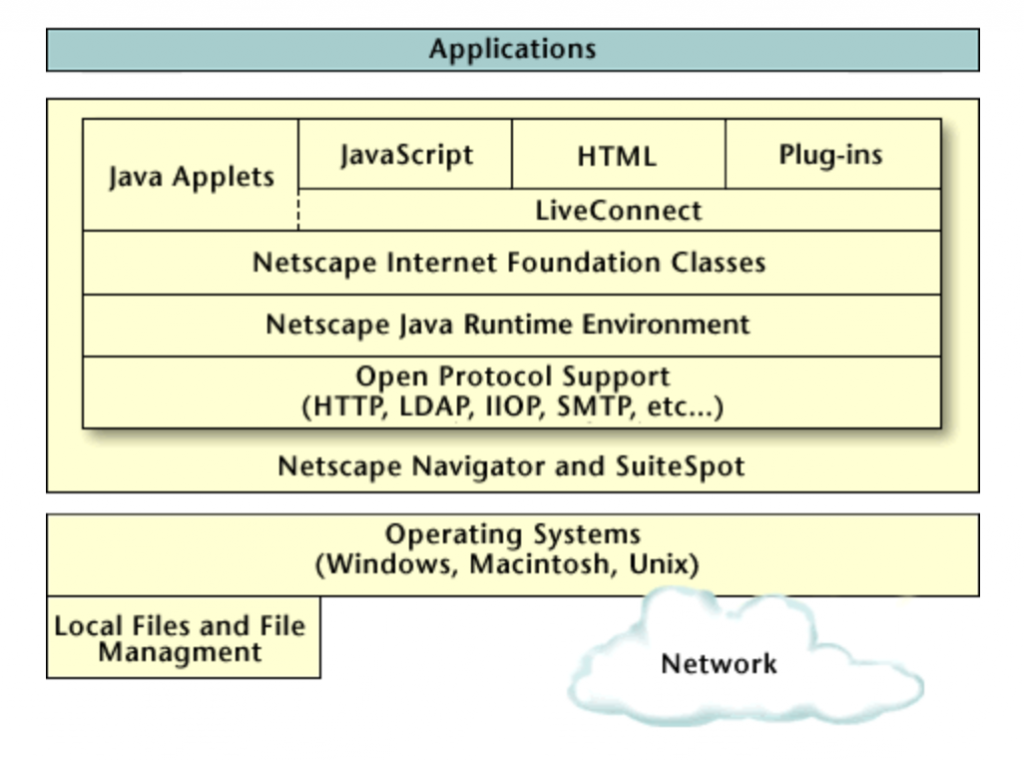

But the key from a developer perspective was the added functionality on the client-side, via the upcoming Communicator platform. Of particular interest for developers was LiveConnect, a new framework that would allow interactive technologies like Java, JavaScript and plugins to be inserted into HTML. LiveConnect would even connect with other interactive scripting languages…although as Andreessen joked in his keynote, that was supported but not encouraged.

“What we do is we use LiveConnect to wire together all the different objects that can be appropriated in HTML. Now with Communicator 4.0, that includes everything from Java and JavaScript objects, [and] we’re gonna provide full support for JavaBeans components, OLE, ActiveX, OpenDoc and other legacy platform specific objects.”

(Cue laughter from the crowd at Andreessen’s emphasis of the word ‘legacy’)

“We still wouldn’t actually suggest that you use them,” Andreessen ad-libbed, clearly referring to the two Microsoft technologies he’d mentioned (OLE and ActiveX).

“The Communicator itself exposes lots of APIs and protocols,” he continued a bit later in the keynote, before listing the various ways that Java developers could create applications for Communicator.

“You can write to the core Java APIs directly, you can also write to the Internet Foundation Classes [and] very quickly piece together Java applications. These IFCs provide Java class libraries that serve as […] prefabricated building blocks for great apps.”

IFCs was a graphics library for Java, which Netscape developed and released in December 1996.

Andreessen finished his keynote by summarizing the state of Netscape from a development perspective.

“Here’s what we’re doing as a basic overview: first, advancing the art of multimedia and HTML; second, enriching the entire Java and JavaScript environment in both the client and server; third, providing the seamless integration with existing desktop and enterprise systems; and fourth, ensuring that developers are able to see and use the benefits of a huge set of very rich tools.”

One example Andreessen cited of the progress in web development that Netscape was enabling was “absolute positioning” of components on a web page. He explained that this was “a brand new capability […] which lets any object in an HTML page — a Java applet, a plug-in, an HTML element, whatever — be positioned anywhere on the screen.” The functionality gave developers “the same degree of control that you’d normally associate with CD-ROM multimedia,” he added.

Inching Towards Web Standards

In November, Netscape announced its plan to standardize JavaScript via the ECMA international standards organization, a European computing standards body. It had only gone to the ECMA after being rebuffed by the web’s official standards keeper, the W3C.

Netscape also offered to “license JavaScript at no charge as part of Netscape ONE, the open network environment.” While the Netscape ONE platform would eventually fall by the wayside, the free license at this point was a key part of JavaScript continuing to gain traction in these early years.

The same press release put some numbers on not only JavaScript adoption, but Java too. The two languages had “seen rapid developer acceptance with more than 175,000 Java applets and more than 300,000 JavaScript-enabled pages on the Internet today according to www.hotbot.com.” That mightn’t seem like much today, but bear in mind the total number of websites in 1996 also numbered in the hundreds of thousands (the web didn’t reach 1 million websites until April 1997).

Conclusion

As this post has shown, 1996 was an ambitious, productive year for Netscape and one of great progress for web development in general. As Marc Andreessen pointed out, browser technology in 1996 had expanded beyond the initial document-focused delivery of websites over 1994 and 1995. In 1996, we began to see web applications emerge — or at least the foundations being set.

Some of this movement towards web apps was possible due to JavaScript, but Java was at the time seen as the superior web programming language. Netscape also carefully positioned itself as a vendor in enterprises, mainly to try and sell its many proprietary server products (which, unlike Navigator, came with price tags).

However, Netscape wasn’t the only one pushing web development forward in 1996. Microsoft had been watching from afar in Redmond as Netscape became the hottest startup in Silicon Valley. After finally registering in 1995 that the internet was a big deal, throughout 1996 Microsoft literally and figuratively shadowed its younger and much smaller rival. It ended up copying not only Netscape’s browser…but its JavaScript language too. We’ll get into that in the next post in this series.